Georges Ekane: The Question Cameroon Must Answer

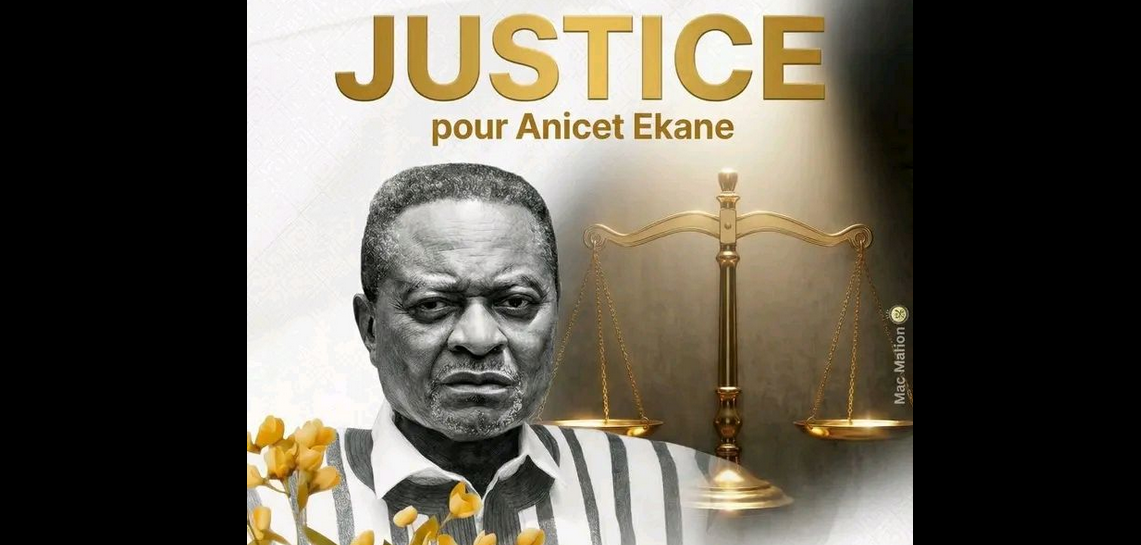

[YAOUNDÉ, Dec 18 – Cameroon Concord] — The death of Georges Anicet EKANE, National President of MANIDEM, has become more than a personal tragedy and more than a partisan dispute. It is now a national test of whether Cameroon still possesses the minimum civic instinct required to ask the hardest question in any republic: who is responsible when a politically exposed citizen dies under state custody?

The text circulating in legal and activist circles is explicit and uncompromising: it describes EKANE’s death as the endpoint of a premeditated political crime, “slowly and cynically executed,” and insists that accountability cannot stop at sympathy, condolence messages, or administrative denials. Whether one adopts that conclusion or approaches it with caution, the public interest remains the same: the chain of responsibility must be mapped, and evidence must be demanded.

This is not about emotional outrage alone. It is about procedures, signatures, orders, custody conditions, medical decisions, and oversight failures. It is about identifying who had the power to prevent harm — and who allegedly used power to enable it.

The First Question: Who Ordered the Arrest?

The core claim is that EKANE was not arrested in a conventional criminal framework. No public record has been presented showing he was caught in flagrante delicto, nor that he was summoned and refused to appear, nor that a lawful warrant was executed in standard form. If he was taken without a valid judicial basis, the act becomes, in legal terms, closer to arbitrary deprivation of liberty — and in political language, it is described as a kidnapping.

In Cameroon, the administration sometimes relies on “public order” logic or exceptional procedures. But exceptional systems still require traceable authority: someone signs, someone authorizes, someone executes, someone logs the custody, someone reports upward.

The text argues that if administrative detention was used, then the likely signatory authority would be territorial command — typically the Governor of Littoral or the Senior Divisional Officer (Prefect) of Wouri. That is where a serious inquiry begins: which office issued the first enabling act? If none exists, the question becomes even more urgent.

The same argument links Cameroon’s international commitments — especially norms against arbitrary detention — to domestic enforceability. The point here is not to litigate international law in a newsroom. The point is practical: if a prior authoritative finding exists that similar arrests were arbitrary, the state cannot pretend the legal risk is unknown. A responsible investigator would therefore compare patterns, documents, and chains of command.

The Second Question: Who Executed an Order They Knew Was Illegal?

Even if an administrative authority signed a document, the second layer is operational: police, gendarmerie, intelligence agents, and officers of the criminal chain who planned and executed the arrest.

EKANE was a known political figure. He was not publicly presented as a violent criminal caught during an active threat. The text insists that those who executed the arrest could not reasonably claim ignorance of the political context and the apparent absence of a standard judicial process.

This is where the issue shifts from “who ordered” to “who complied.” In law and ethics, “I was following orders” is not a shield when the order is manifestly unlawful. A serious investigation would therefore identify:

-

the unit(s) involved,

-

the commanding officer(s) on duty,

-

the written operation instructions (if any),

-

custody logs, transport logs, and handover signatures,

-

communications between local command and central structures.

Names cited in the submitted text (including senior gendarmerie figures) are allegations that would require evidentiary testing, not repetition as proven fact. Cameroon Concord’s responsibility is to reflect the claim accurately while maintaining the legal distinction: alleged involvement is not proven culpability.

The Third Question: Who Decided the Transfer to Yaoundé and the Military Track?

A major escalation alleged in your submission is the “deportation” (transfer) from Douala to Yaoundé, followed by placement under procedures linked to military justice structures.

That shift matters because moving a politically exposed civilian into a security-heavy chain can create conditions where oversight weakens and abuse risk increases. The submitted text asserts a chain: military prosecution structures, military justice directorate, delegated defense authority, and ultimately the constitutional reality that defense is controlled at the highest executive level.

Again, the journalistic task is not to declare guilt but to outline the accountability map:

-

Who authorized the transfer?

-

Under what legal instrument?

-

On what charge and under what jurisdiction?

-

Who received the detainee?

-

Who controlled custody during interrogation and detention?

-

Who authorized continued detention, and what review existed?

If the detainee was held without a valid judicial mandate, that becomes a separate layer of illegality — and potentially criminal liability for unlawful detention.

Health Status, Oxygen, and the Line Between Neglect and Harm

The submitted text anchors one of its strongest arguments on EKANE’s known medical condition — specifically the alleged removal or denial of a vital oxygen device and failure to provide appropriate medical care.

This is not a small detail. In custody cases worldwide, medical decisions are often the difference between a lawful detention and a lethal one. If a detainee is known to be medically fragile, every authority in the chain inherits a duty of care:

-

arresting officers,

-

the custody commander,

-

the investigating unit leadership,

-

medical staff assigned to the detention site,

-

any supervising prosecutor or authority notified of risk.

If a vital device was withheld, delayed, or intentionally kept away, the legal characterization can move from negligence to something far heavier depending on evidence: reckless endangerment, failure to assist a person in danger, or intentional harm. The submitted text alleges deliberate intent; the minimum standard for state credibility is to produce transparent medical documentation and custody logs rather than blanket denials.

The Clinic at Camp Yeyap: Why the Facility Matters

Another crucial point in your submission is the dispute over where EKANE died — a clinic/infirmary at the gendarmerie camp (Yeyap), not the military hospital as allegedly claimed publicly by defense authorities.

This distinction is not cosmetic. It determines:

-

the available equipment level,

-

standard referral protocols,

-

who controlled access,

-

whether the patient should have been transferred to a higher-level facility,

-

and whether the care setting matched the severity of his condition.

If a detainee in critical condition remained in a low-capacity setting while higher-level hospitals were nearby, any inquiry must ask: who decided not to refer him, and why? Medical staff cannot hide behind institutional loyalty when a life is on the line. If referral protocols exist, they must be produced. If they were ignored, accountability follows the decision, not the excuse.

Oversight Failure: Who Knew and Did Nothing?

Your submission further alleges that lawyers, family, and civil society issued public alerts — implying that multiple authorities had notice of deteriorating health and risk of death.

That introduces a different kind of responsibility: not just who acted, but who failed to act.

A credible investigation would therefore summon:

-

detention administrators who received complaints,

-

human rights institutions that were notified,

-

judicial authorities with oversight powers,

-

senior security officials who received reports,

-

and any public authority that made statements contradicting the custody reality.

When institutions are warned and remain inert, they do not remain neutral. In law, inaction can become complicity when a preventable harm unfolds.

Why “Investigation” Cannot Mean Self-Investigation

The submitted text argues that an investigation led by the same structures accused in the matter cannot be credible, especially where military justice and gendarmerie custody intersect.

This is a central credibility problem: if the same chain of command that controlled custody also controls the inquiry, the public will assume the outcome is pre-written.

A credible path, at minimum, would require:

-

independent forensic process,

-

secure preservation of custody evidence,

-

transparent publication of key documents (within legal limits),

-

access for legal representatives,

-

and a mechanism preventing suspects from directing investigative steps.

Without this, “investigation” becomes an administrative ritual used to bury the question rather than answer it.

The Real Stakes: One Man, or the Rule of Law?

The EKANE case is not only about one political leader, however prominent. It is about whether Cameroon accepts a future where political custody can quietly become a death sentence — or whether the country still insists that the state must be bound by law even when it feels threatened by dissent.

If the state is confident in its legality, it should welcome clarity: show the mandate, show the custody logs, show the medical file, show referral decisions, show the chain of orders. If it is not confident, silence and deflection will only deepen public suspicion.

In the end, the question remains brutally simple: who signed the first step, who enforced it, who managed custody, who controlled medical care, and who decided to let a man die under state control?

That is what Cameroon now waits to learn — not in slogans, but in documents, testimony, and accountability.

- Details

- News Team

- Hits: 2991