In Defence of the Common Law: A Lawyer's suggestions to lawyers

On February 13th 2016, lawyers of the Common Law extraction in Cameroon shall converge in Buea for another conference. Of course top on the agenda will be to address the moves currently been taken by some overzealous administrative and judicial authorities to annihilate the common law in Cameroon. At this point, I cannot but jump in to attempt a proposal as to what should be on our minds during that conference. In that vein, I wish to remind my colleagues about the learned Barrister Chief Charles AchalekeTakuon the occasion of the society’s inaugural meeting in Bamenda on Jan 28 2012. On that day, Chief Taku in his keynote addresssaid “…some misguided and gullible political leaders miscomprehend unity (of the two Cameroons) with uniformity and see every facet of public life that promotes and protects freedom and a free society as a threat to their political power.For this reason, they evinced every effort to short-circuit and abort the development and survival of the common law system that has governed much of the free world for centuries. To attain this goal, they put in place a deliberate amorphous system so-called ‘harmonization’, whose purport is to create confusion, put … the common law system under constant threat, then destabilise, and impose a preconceived substitute with an enslaving agenda”.

The common law, “… a system that guarantees judicial remedies like Habeas Corpus, Certiorari, Prohibition, Mandamus and made bail a right rather than a privilege, threatens executive lawlessness and dictatorship,” the erudite and eloquent Chief Taku continued.

At this juncture, the history of the sad and sorry union between the Cameroons comes to mind. Every true chronicler of the Cameroon situation remembers those institutions of Former West Cameroon… Powercam, Cameroon Bank, the West Cameroon Police Force, etc., amongst others that have been killed by the ‘other’ Cameroon. One thinks of how the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so-called union watch helplessly as their kith and kin are being reduced daily, to second-class citizens. Then I ask; will the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer sit quiet and watch how the tool with which he is supposed to defend his clients, is being eroded and taken away from him? If the Cameroon Common Law Lawyer does not stand up against this, would he be able to stand up for his client? With what? The answers that ruminate to mind, send climes of chilly self-annihilating steps back home and propel me to join Chief Taku and the common law lawyers that are to converge in Bamenda to say an emphatic NO!

I further suggest that the Cameroon common law lawyer must reclaim the ethical legacy of noble lawyers past and neophyte lawyers must be schooled in that wisdom and professional justification. I make bold to state that the current process of harmonization of laws between the civil law and the common law in Cameroon is an attempt at suppressing the latter, to the point of even killing it. As such, while in Bamenda or anywhere in the future, the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer should be able to stand and remain standing while hurling anathemas on the assimilating system which now comes under the disguised form of the so-called harmonisation. The Cameroon common law lawyer must not be like Chinua Achebe’s proverbial adult, who sits and watches the she goat suffer under the pains of child birth. He must be able to say that there is no way that laws and procedures that are to be used in two distinct legal systems could ever be harmonised and be expected to thrive as separate entities. No!

Nowhere in human history has the civil law and common law, be it in their adjectival or procedural forms, have been harmonised! It does not work like that. It has never. And so, shall it never work! There have been classic biases and atrocities committed against the common law system in this country. But lately, the perpetrators of these heinous crimes have executed a sudden somersault with apologies that the real intention is not to exterminate the common law system, but to harmonise the two systems in the now “one Cameroon’. The fact that this traditional adversarial image (as opposed to the French civil law system), still has great currency in the legal profession the world over, has much to do with the equally traditional theory of law from which it draws its shape and justification. For better or for worse, the hallmark is found in their cultivation of rule-craft, -the ability to identify the extant rules of the legal system and apply them to particular situations. The central article of faith of this traditional positivism is that rules are the basic currency of legal transactions and their application can be performed in a professional and objective way.

In my book, the common law is an imposing (and should remain) an imposed structure that has considerable stability, that is operationally determinate in the guidance it extends to the trained lawyer and that is institutionally distinct from the more open-minded disputations around ideological politics. As such, the image of the lawyer-as-hired-hand embraces the idea that the common law in Cameroon, like everywhere in the world, has a life of its own and should neither be politically-myth-informed, nor influenced by governmental policy makers and (mis)managers.

In this sense, any practice that craves and expects professional recognition must be seen to take the common law seriously in the sense that it pursues clients’ interests through extant rules, procedures and values of law: overt politicisation is severely frowned at. Again, in my book, this is a proud unapologetic and defiant defence of the Rule of Law which must now become pax-Kamaruna. And if this must be, then it must be the face of the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer.

The common law lawyer in Cameroon today must cut a niche for himself. He must stand out clearly in exhibition of the notion of the lawyer as a civic campaigner. He must build a pyramid of honour, probity and humaneness and impose himself up there, especially in the face of the present condition of the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so called union of the two Cameroons. He must be a goad and a gadfly to his suffering kith and kin. The common law lawyer must speak out against bribery and corruption, stand for the down-trodden and defend his kindred who are now caught up in this quagmire of Quisling-Iscariots. (I have taken liberties here with the late Dr. Bate Besong of the ObassinjomWorrior fame). Oh yes, we must deny to be Heweit! Litigation and adjudication are much more value-laden and results-oriented than traditionalists suppose. Consequently, the common law lawyer must take an appropriate share of the responsibility for those values and results. At the very least, he must engage in the struggle to make the legal process the best that it can be for the benefit of those who live under its directives, particularly the disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

As much as lawyers are officers of the law, they are also agents of the people: they cannot afford to sit quiet in the face of such blatant rape being meted out with impunity and excruciating pain against their lot and institutions. With our present situation, the Cameroon common law lawyer cannot assume a non-committal position. He must be militant and assume a much more pedestrian approach in defence of the law. My take is that the Cameroon judicial system has much to emulate from the Canadian experience. Like Cameroon, Canada is both bilingual and bi-jural. While the civil law system, informed by the codified Napoleonic laws obtains in the Francophone region of Canada, the common law system obtains in Anglophone Canada. These two have co-existed ever since the Canadian Federation was founded.

None of the two systems has attempted to swallow or engulf the other! Both the Common law and the civil law thrive side-by-side, and so well in Canada. So why can it not be so in the Cameroons? The civil law and the common law are like equity and the law itself. Professor Kisob I remember once said that they are like two streams that run through the same channel but their waters don’t mix. This is the sermon that the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer must preach ex-cathedra, to the powers that be! In July 1995, 16 French speaking countries in Africa ratified the OHADA Treaties. These treaties were to harmonize business law in Africa. Cameroon was amongst them. All of these countries have the civil law system as their system of law. The law stated that the working language of the OHADA was French. As expected, the Yaounde junta attempted to have this law operate in English speaking Cameroon, but the common law lawyers (from both the bench and the bar) stood like one man and said NO!They objected to the applicability of the OHADA as it was. Not long, English language was added as another working language of the said law. This was a eureka moment for the common law system in Cameroon. If the common law lawyer could force the English language on the French speaking countries of the sub-region, then it can stop the wanton rape now being done on its system of law practice. Yes we can.

* Parts of this article were first published in The NewBroom Magazine. Its author, TANYI-MBIANYOR SAMUEL TABI is a Common Law Lawyer who read law in Toronto and Yaounde. A member of both the Cameroon and Canadian bar Associations, he is currently a research student at Walden University.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 4179

Local News

- Details

- Society

Kribi II: Man Caught Allegedly Abusing Child

- News Team

- 14.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Back to School 2025/2026 – Spotlight on Bamenda & Nkambe

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Cameroon 2025: From Kamto to Biya: Longue Longue’s political flip shocks supporters

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Meiganga bus crash spotlights Cameroon’s road safety crisis

- News Team

- 05.Sep.2025

EditorialView all

- Details

- Editorial

When Power Forgets Its Limits: Reading Atanga Nji Through Ekinneh Agbaw-Ebai’s Lens

- News Team

- 17.Dec.2025

- Details

- Editorial

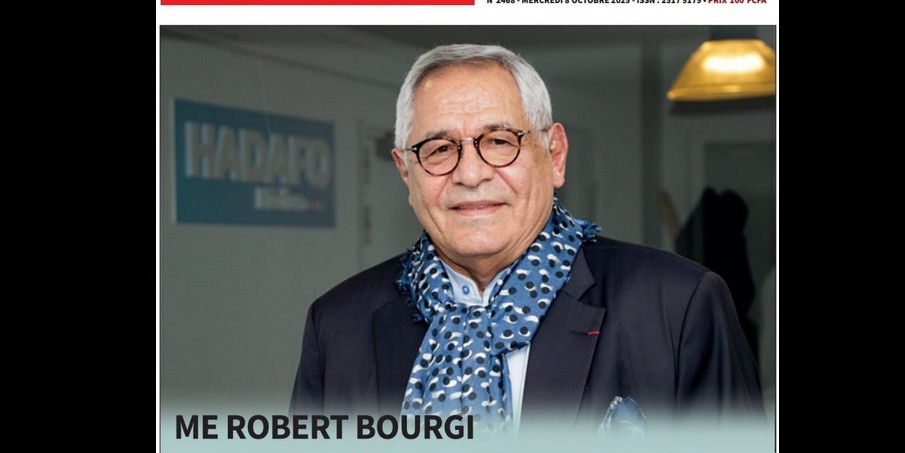

Robert Bourgi Turns on Paul Biya, Declares Him a Political Corpse

- News Team

- 10.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Heat in Maroua: What Biya’s Return Really Signals

- News Team

- 08.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Issa Tchiroma: Charles Mambo’s “Change Candidate” for Cameroon

- News Team

- 11.Sep.2025